I. Introduction

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a life-saving technique that can mean the difference between life and death for victims of cardiac arrest. When performed correctly, CPR can maintain blood flow to vital organs, buying precious time until professional medical help arrives. However, the effectiveness of CPR hinges on proper technique and timely application.

In recent years, a significant shift has occurred in CPR methodology, placing greater emphasis on what is known as the CAB approach. This method has become the cornerstone of effective CPR, revolutionizing how we respond to cardiac emergencies. In this article, we’ll explore why CAB is crucial for maximizing the chances of survival in cardiac arrest situations.

II. Understanding CAB

The CAB approach refers to the sequence of actions in CPR:

C – Compressions A – Airway B – Breathing

This order represents a departure from the traditional ABC (Airway, Breathing, Compressions) method that was standard practice for decades. The shift to CAB wasn’t arbitrary; it was based on extensive research and real-world evidence that demonstrated its superior effectiveness.

The CAB approach prioritizes chest compressions as the first and most critical step in CPR. This change reflects our evolving understanding of what happens during cardiac arrest and how we can best intervene to save lives.

Historically, the ABC method was taught as the standard approach to CPR. Rescuers were instructed first to open the airway, then provide rescue breaths, and only then begin chest compressions. While this method had its merits, research showed that it often led to delays in starting chest compressions, which are crucial for maintaining blood flow to vital organs.

The shift to CAB came about in 2010 when the American Heart Association (AHA) updated its guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. This change was based on compelling evidence that immediate chest compressions are the most important factor in improving survival rates from cardiac arrest.

By starting with compressions, the CAB approach ensures blood circulation begins as quickly as possible. This is critical because, during cardiac arrest, the blood stops flowing, and oxygen-rich blood remains in the arteries. Immediately starting chest compressions can circulate this oxygenated blood to the brain and other vital organs, potentially preventing irreversible damage.

Moreover, the CAB approach simplifies CPR for lay rescuers. Many people hesitate to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, especially on strangers. By emphasizing compressions first, CAB removes this potential barrier to action, encouraging more bystanders to step in and perform CPR when needed.

III. Compressions: The “C” in CAB

Chest compressions form the foundation of effective CPR and are the first step in the CAB approach. Their importance cannot be overstated, as they are crucial for maintaining blood flow to vital organs during cardiac arrest.

A. Importance of immediate chest compressions

When the heart stops beating, blood flow ceases, depriving the brain and other vital organs of oxygen. Brain damage can begin within minutes of oxygen deprivation. Chest compressions manually pump blood through the body, providing a lifeline of oxygen to these critical organs. By starting compressions immediately, we can significantly improve the chances of survival and reduce the risk of permanent brain damage.

B. Proper technique for chest compressions

Effective chest compressions require proper technique:

- Position: The victim should be lying on their back on a firm, flat surface.

- Hand placement: Place the heel of one hand on the center of the victim’s chest, with the other hand on top.

- Body position: Keep your arms straight and position your shoulders directly over your hands.

- Compression motion: Push hard and fast, allowing the chest to fully recoil between compressions.

C. Rate and depth of compressions

The American Heart Association recommends:

- Rate: Aim for 100-120 compressions per minute. This fast pace helps maintain adequate blood flow.

- Depth: For adults, compress the chest at least 2 inches (5 cm) but not more than 2.4 inches (6 cm). For children, the depth should be at least one-third the anterior-posterior diameter of the chest.

D. Minimizing interruptions

Continuous chest compressions are vital. Any interruption in compressions results in an immediate drop in blood pressure, reducing the effectiveness of CPR. Rescuers should aim to minimize pauses between compressions, even when switching rescuers or preparing to use an automated external defibrillator (AED).

The emphasis on compressions in the CAB approach addresses a critical flaw in the older ABC method. In the ABC approach, precious time was often lost in attempting to open the airway and deliver rescue breaths before starting compressions. By prioritizing compressions, CAB ensures that blood circulation begins as quickly as possible, maximizing the chances of survival.

Research has shown that high-quality chest compressions are the most critical factor in successful CPR. A study published in the journal “Circulation” found that continuous chest compressions were associated with improved survival rates compared to standard CPR with pauses for ventilation.

IV. Airway: The “A” in CAB

After initiating chest compressions, the next step in the CAB approach is managing the airway. While this comes second in the sequence, it remains a crucial component of effective CPR.

A. Opening the airway

An open airway is essential for effective ventilation. When a person loses consciousness, the muscles in their neck and tongue relax, potentially obstructing the airway. Opening the airway ensures that air can flow freely into the lungs during rescue breaths or spontaneous breathing.

B. Head-tilt chin-lift technique

The most common method for opening the airway in an unconscious person is the head-tilt chin-lift technique:

- Place one hand on the victim’s forehead and gently tilt the head back.

- With the other hand, lift the chin by placing your fingers on the bony part of the lower jaw.

- Avoid pressing on the soft tissues under the chin, as this can obstruct the airway.

This maneuver lifts the tongue away from the back of the throat, clearing the airway.

C. Jaw-thrust maneuver for suspected neck injuries

In cases where a neck injury is suspected (such as in trauma situations), the jaw-thrust maneuver is preferred:

- Place your hands on either side of the victim’s head, with your fingers under the angles of the lower jaw.

- Lift the jaw forward without tilting the head back.

This technique opens the airway while minimizing neck movement, reducing the risk of exacerbating a potential spinal injury.

The placement of airway management as the second step in CAB, rather than the first as in the ABC approach, reflects a crucial shift in CPR priorities. This change acknowledges that in the first few minutes of cardiac arrest, there is often enough oxygen in the bloodstream to sustain vital organs if circulation is maintained through chest compressions.

By addressing the airway after initiating compressions, the CAB approach ensures that blood circulation begins immediately while still recognizing the importance of airway management for ongoing resuscitation efforts.

It’s important to note that for trained healthcare providers performing two-rescuer CPR, one rescuer can begin chest compressions while the other simultaneously manages the airway, further optimizing the resuscitation process.

V. Breathing: The “B” in CAB

The final component of the CAB approach is breathing, which involves providing rescue breaths to the victim. While chest compressions are prioritized, rescue breathing remains an important part of CPR, especially in prolonged resuscitation efforts.

A. Rescue breath technique

Once the airway is open, rescue breaths can be administered:

- Pinch the victim’s nose closed with your thumb and index finger.

- Take a normal breath and cover the victim’s mouth with yours, creating a seal.

- Give one breath lasting about 1 second, watching for the chest to rise.

- If the chest doesn’t rise, reposition the head and try again.

- Give a second breath.

B. Ratio of compressions to breaths

For adult CPR, the recommended ratio is:

- 30 compressions to 2 breaths for single-rescuer CPR

- 30 compressions to 2 breaths for two-rescuer CPR

For child and infant CPR, trained rescuers should use a 15:2 ratio in two-rescuer situations.

It’s crucial to minimize interruptions to chest compressions when giving breaths. Each set of two breaths should take no more than 10 seconds.

C. Use of barrier devices

To reduce the risk of disease transmission, rescuers can use barrier devices such as:

- Pocket masks: These provide a seal over the victim’s mouth and nose, with a one-way valve for rescue breaths.

- Bag-valve-mask devices: Used primarily by healthcare professionals, these allow for more controlled ventilation.

The placement of breathing as the final step in CAB underscores a significant shift in CPR philosophy. In the early stages of cardiac arrest, the blood often contains enough residual oxygen to sustain vital organs if circulated effectively through chest compressions. By delaying rescue breaths, CAB ensures that life-saving compressions begin immediately.

However, it’s important to note that in certain situations, such as drowning or drug overdose, where the primary issue is respiratory failure leading to cardiac arrest, providing rescue breaths earlier may be beneficial.

For lay rescuers who are untrained or uncomfortable with rescue breaths, hands-only CPR (compressions without breaths) is recommended. Studies have shown that hands-only CPR can be as effective as traditional CPR in the first few minutes of a sudden cardiac arrest.

The CAB approach, by prioritizing compressions and simplifying the process, has made CPR more accessible to lay rescuers while maintaining its effectiveness. This has the potential to increase bystander CPR rates, which is a critical factor in improving survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

VI. Why CAB is More Effective Than ABC

The shift from the ABC (Airway, Breathing, Compressions) method to the CAB (Compressions, Airway, Breathing) approach represents a significant advancement in the CPR technique. This change is based on scientific evidence and practical considerations that demonstrate CAB’s superior effectiveness.

A. Faster blood circulation to vital organs

The primary advantage of CAB is the immediate initiation of chest compressions. In cardiac arrest, the critical issue is the lack of blood flow to vital organs, particularly the brain. By starting with compressions, CAB ensures that oxygenated blood in the arteries is circulated as quickly as possible. This rapid response can significantly reduce the risk of brain damage and increase the chances of successful resuscitation.

In contrast, the ABC method often led to delays in starting compressions while rescuers focused on opening the airway and providing initial breaths. These delays, even if only for a few seconds, could be critical in the early stages of cardiac arrest.

B. Reduced delay in starting compressions

Studies have shown that in the ABC approach, there was often a significant delay before chest compressions began. This delay occurred for several reasons:

- Time spent checking for breathing

- Difficulty in opening the airway

- Reluctance or inability to perform mouth-to-mouth resuscitation

By prioritizing compressions, CAB eliminates these initial delays. Rescuers can start chest compressions almost immediately upon recognizing cardiac arrest, maximizing the time spent circulating blood.

C. Simplification of the process for lay rescuers

The CAB approach simplifies CPR for lay rescuers in several ways:

- Clear starting point: Beginning with compressions provides a clear, unambiguous first step.

- Overcoming hesitation: Many people are uncomfortable with or unsure about giving rescue breaths, especially to strangers. By emphasizing compressions first, CAB removes this potential barrier to action.

- Easier to remember: The simplicity of “start with compressions” makes the process easier to recall in high-stress situations.

This simplification is crucial because bystander CPR is a key factor in survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. By making CPR more accessible and less intimidating, CAB potentially increases the likelihood of bystander intervention.

The effectiveness of CAB over ABC is not just theoretical. Multiple studies have demonstrated improved outcomes with the CAB approach. For example, a study published in the journal “Resuscitation” found that the CAB approach resulted in a shorter time to first compression and a higher number of compressions delivered compared to the ABC method.

Moreover, the American Heart Association’s shift to recommending CAB in 2010 was based on a comprehensive review of available evidence. This change reflected a growing consensus in the medical community about the critical importance of early, high-quality chest compressions in improving survival rates from cardiac arrest.

VII. Scientific Evidence Supporting CAB

The transition from ABC to CAB in CPR guidelines wasn’t made lightly. It was based on robust scientific evidence and extensive research. This section explores the key studies and guidelines that support the effectiveness of the CAB approach.

A. American Heart Association guidelines

The American Heart Association (AHA) first recommended the CAB approach in its 2010 Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. This marked a significant shift in CPR protocol. The AHA’s decision was based on several factors:

- Recognition of the critical importance of chest compressions

- Evidence that delays in starting compressions decreased survival rates

- Data showing that blood oxygen levels remain adequate for the first few minutes of CPR without rescue breaths

The AHA continues to support the CAB approach in its subsequent guideline updates, reinforcing its effectiveness.

B. Research studies comparing CAB to ABC

Numerous studies have compared the CAB and ABC approaches, consistently finding advantages to the CAB method:

- Time to first compression: A 2013 study published in “Resuscitation” found that the CAB approach resulted in chest compressions starting approximately 20 seconds earlier than with the ABC method.

- Number of compressions delivered: The same study showed that significantly more chest compressions were performed in the first minute with CAB compared to ABC.

- Simplicity and ease of learning: A 2012 study in the “Journal of Emergency Medicine” demonstrated that CAB was easier for lay rescuers to learn and perform correctly compared to ABC.

- Willingness to perform CPR: Research published in “Circulation” in 2010 indicated that bystanders were more willing to perform hands-on CPR (which aligns with the CAB approach) than traditional CPR with rescue breaths.

C. Improved survival rates with the CAB approach

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for CAB comes from studies examining survival rates:

- A large-scale study published in “JAMA” in 2013 analyzed over 5,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. It found that patients who received chest compression-only CPR (aligned with CAB) had a significantly higher chance of survival with good neurological outcomes compared to those who received standard CPR.

- A meta-analysis published in “The Lancet” in 2010 reviewed multiple studies involving nearly 4,000 cardiac arrest patients. It concluded that chest compression-only CPR was associated with improved survival compared to standard CPR with rescue breaths.

- A 2017 study in the “Journal of the American College of Cardiology” found that the implementation of the CAB approach, along with other updates to resuscitation guidelines, was associated with increased survival rates for in-hospital cardiac arrests.

These studies collectively provide strong evidence for the superiority of the CAB approach in improving outcomes for cardiac arrest victims. The consistent findings across various research settings and methodologies underscore the robustness of this evidence.

It’s important to note that while these studies strongly support CAB, research in resuscitation science is ongoing. Scientists and medical professionals continue to refine and optimize CPR techniques to further improve survival rates and outcomes for cardiac arrest victims.

VII. Conclusion

In summary, the CAB approach—Compressions, Airway, Breathing—stands as the cornerstone of effective CPR, ensuring that oxygenated blood circulates to vital organs and increases the chances of survival during cardiac emergencies. Mastering this lifesaving technique is not only crucial for healthcare professionals but also for everyday citizens who might find themselves in a position to save a life.

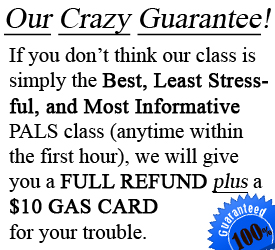

Don’t wait until it’s too late. Equip yourself with the skills and confidence to act in an emergency by enrolling in a CPR certification course. For those in the Tampa area, CPR certification in Tampa offers comprehensive training that follows the latest guidelines and best practices.

Take the first step towards becoming a lifesaver today. Sign up for CPR Classes Tampa and be prepared to make a difference when it matters most!